News

Who were the real courtesans at the heart of Netflix’s Heeramandi?

Indian director Sanjay Leela Bhansali is thought for his big-budget Bollywood manufacturing, that includes grand units, star casts, meticulously choreographed dance sequences and lavish costumes, jewelry and furnishings. His new collection for Netflix, Heeramandi: The Diamond Bazaar, lives as much as these expectations.

In opposition to this visually wealthy backdrop emerge the scheming, menacing and murderous courtesans of Heeramandi.

The collection is about in Heeramandi, a historic red-light district of Lahore in present-day Pakistan. It unfolds in opposition to the backdrop of the Indian freedom battle in opposition to British rule.

The present is an entanglement of plot strains – a homicide investigation, a struggle of succession, a budding love story and a courtesan’s secret involvement in a revolt in opposition to British rule.

Ultimately, all characters and storylines converge across the central theme of anti-colonial nationalism. Pushed by nationalist fervour, the courtesans name themselves “patriots” and willingly sacrifice their careers and lives for the nation.

However who had been the true courtesans?

Position fashions for feminine independence

The present takes artistic liberties by distorting the lives and timelines of the historic courtesans.

The North Indian tawa’ifs (courtesans), or nautch-girls (dancing ladies, because the British referred to as them), had been cultural idols, feminine intellectuals and entrepreneurs.

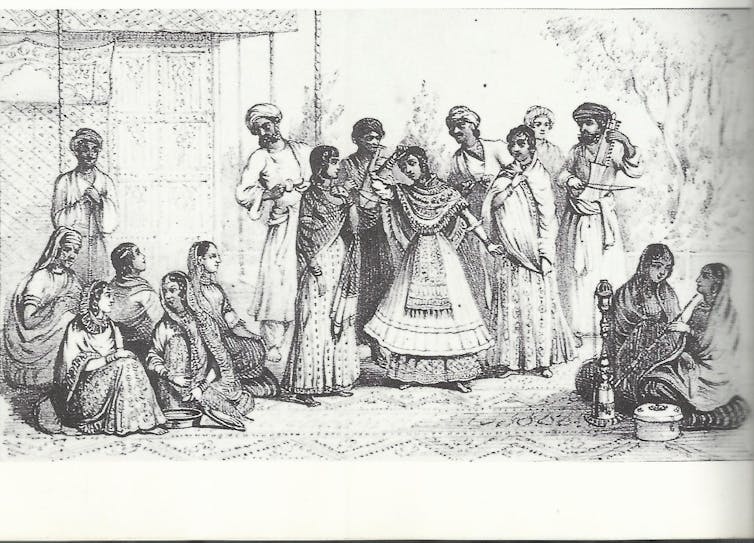

Courting again to historic India, these ladies had been skilled in music, dance, style, poetry, repartee, etiquette, languages and literature from a younger age. Sometimes following a system of matrilineal inheritance, courtesans handed down their skilled information and expertise to gifted daughters of the family.

Wikimedia Commons

As soon as skilled, courtesans attracted patronage from royal courts, feudal aristocrats and colonial officers.

This distinctive class loved privileges not afforded to most ladies in Indian society, equivalent to training and private revenue. They led glamorous life, wielded energy and wealth, and paid taxes.

As impartial professionals, they contributed to Indian arts and tradition, travelled extensively, made connections with chosen kin and sometimes embraced gender fluidity.

Courtesy Anindya Banerjee

Their monetary, political and sexual independence challenged patriarchal gender norms and restrictive Hindu ethical legal guidelines that dictated the lives of girls from upper-middle-class households.

Difficult relationships

In Heeramandi, the courtesans flip patriotic to avenge the British law enforcement officials for raping and killing the natives. Whereas these actions are dramatic, the historic relationship between courtesans, the British empire and Indian nationalism was extra complicated.

The politically engaged Bibbojaan (Aditi Rao Hydari) mirrors Azizan Bai, a courtesan from Kanpur who is alleged to have financially supported the 1857 mutiny in opposition to the British East India Firm.

Whereas the mutiny was one of the vital widespread anti-colonial revolts of the nineteenth century, Indian nationalism was not its main goal, however a consequence. Azizan’s curiosity was in sustaining her patronage from the native rulers for her social and financial wellbeing.

After 1857, India’s governance shifted from the East India Firm to the Crown, resulting in the unfold of British rule throughout India alongside Western training and Victorian morality. In the meantime, nationalist leaders envisioned a nation as a pure land of sacred Hindu ancestors and valued chastity in ladies.

Each the imperial and nationalist beliefs clashed with the courtesans’ sexual freedom.

British Library/Wikimedia Commons

Within the Eighteen Nineties, Hindu reformers and bourgeois nationalists joined Christian missionaries in organising anti-nautch campaigns that advocated boycotting them to “rescue” artwork and tradition from perceived immorality. This led to the downfall of the courtesan class.

In Heeramandi, patronage diminishes and the ladies’s goals of marriage fade. The courtesans shut down their salons, hand over their careers and sacrifice their lives for the nation.

However historic courtesans had been fast to reinvent themselves within the face of declining patronage and social stigma.

They turned to the ability of contemporary know-how. Gauhar Jaan, a well-known courtesan, turned a celebrated live performance singer and gramophone artist, incomes the title of “India’s Melba” within the worldwide press.

In 1921, Gandhi requested Gauhar Jaan to carry out for the Swaraj Fund. Conscious of the ambiguous place courtesans held in nationalist discourse, she agreed on the situation that Gandhi attend her efficiency. When Gandhi failed to indicate up, she contributed solely half of the raised quantity to the trigger.

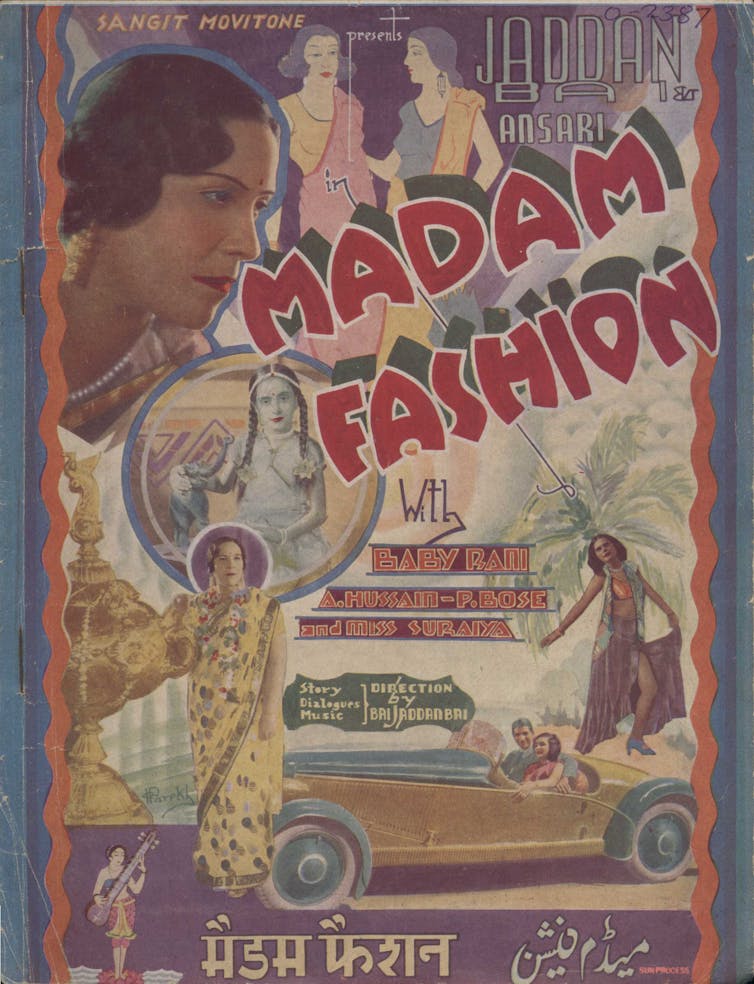

Courtesans contributed considerably to the founding of the Indian movie trade by way of their artistry, star energy and capital funding. The primary era of feminine movie stars got here from courtesan backgrounds: Jaddan Bai, Kajjan Bai, Akhtaribai Faizabadi and Naseem Banu entered the trade as actors, singers, composers, administrators and studio house owners.

Courtesy NFAI

Later, some acted as managers and costume designers for his or her daughters, the rising actors of the following era.

By turning into modern-day artists, the courtesans preserved their artwork. They remained seen and related in a society that was more and more obliterating ladies’s cultural contributions and diminishing their function as residents in an rising nation.

Patriarchal nationalism

Within the present, a girl’s worth is judged by her respectability, marital standing and the presence of a male guardian controlling her sexuality. Courtesans seek advice from themselves as “birds in gilded cages” and dream of freedom from their courtesan life-style.

Netflix

Right here, the courtesans’ nationalism resonates with present-day far-right Hindu nationalists, seemingly promising ladies empowerment in nationalism however, in actuality, reserving solely regressive roles for ladies.

Heeramandi oversimplifies the multilayered persona of tawa’ifs. The collection portrays them as melancholic victims craving for patriarchal married bliss, whereas remaining marginalised in respectable society. However these ladies must be remembered as celebrated figures stuffed with joie-de-vivre, gusto and spiritedness.

They need to be honoured for his or her methods of self-representation and processes of self-determination, as they turned resilience right into a lifestyle.

-

News4 weeks ago

News4 weeks agoHurricane Beryl maps show path and landfall forecast

-

News4 weeks ago

News4 weeks agoIs Simone Biles married? What to know about the Olympic medalist

-

News3 weeks ago

News3 weeks agoPortugal vs. France, picks, odds, live stream, lineup prediction: Where to watch Euro 2024 online, TV channel

-

News3 weeks ago

News3 weeks agoKeKe Jabbar, star of Love & Marriage: Huntsville, dead at 42

-

News4 weeks ago

News4 weeks agoUFC 303: Alex Pereira rocks Jiří Procházka with head-kick KO to defend light heavyweight belt

-

News4 weeks ago

News4 weeks agoExclusive: Google says it cracked down on Chrystia Freeland deepfakes

-

News4 weeks ago

News4 weeks agoChristian McCaffrey Marries Olivia Culpo in Rhode Island Wedding

-

News4 weeks ago

News4 weeks agoOilers trade up to draft Sam O’Reilly with last pick of 1st round